Fiona Apple’s Fetch the Bolt Cutters is the unofficial album of the pandemic. – Slate

[ad_1]

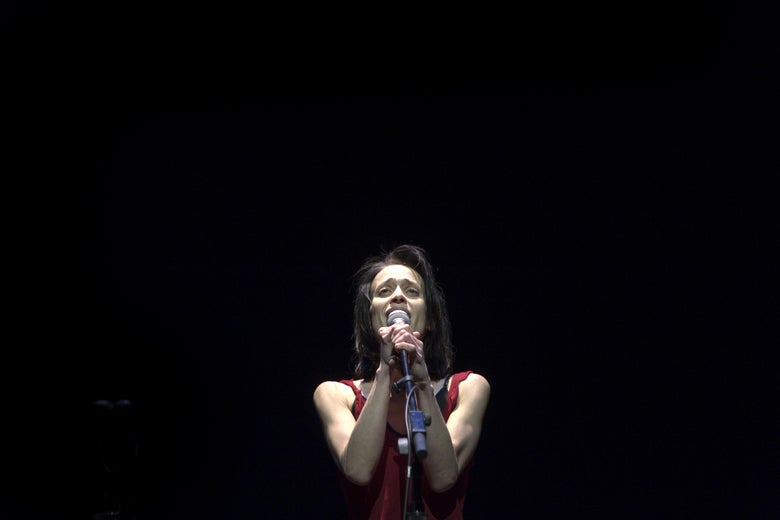

Natalie Behring/Getty Images

At the moment when much of the world is isolating indoors, Fiona Apple has come to break us out. Much of Fetch the Bolt Cutters, Apple’s first album in eight years and only her third in 20, was recorded in her home, its songs built up from clattering percussion tracks that sound as if they could have been pulled together using household objects. Barking dogs and the occasional mewing cat—sounds that have lately become more familiar to many of us than ever—barge in as if she’s left the studio door ajar, and sometimes strange, unidentifiable sounds leak in at the edges, as if her neighbors have left the TV on too loud. It’s an album about confinement, but also about escaping from it, and how even when you’re alone, by circumstance or by choice, the world is never far away.

In a New Yorker profile last month, Emily Nussbaum wrote that Apple “rarely leaves her tranquil house, in Venice Beach, other than to take early-morning walks on the beach with [her dog] Mercy.” Fetch the Bolt Cutters’ title comes from a scene in the British crime show The Fall, and the lyrics to the song “Heavy Balloon” were inspired by the Showtime series The Affair, which means Fiona Apple has been spending the past eight years the way you and I have been spending the past month: sitting inside and binge-watching TV. She’s also been stewing over her past, like the childhood bully who taunts her in “Shameika,” or the “cool kids” in the title track who “voted to get rid of me” and “stole my fun.” But she’s not just perseverating or picking at old wounds. She’s writing as someone who’s learned that the only way out is through, and even after decades, it can feel like the journey is just beginning.

Apple has been hinting at Bolt Cutters’ release for a year, so it can’t really be classed with the recent boomlet in socially isolated art, but her decision to release it when so many artists have pushed their spring releases to fall feels both generous and purposeful, and the reaction has been gratitude verging on canonization. I had to scour my social feeds for so much as a single hedged comment about the album, which Pitchfork awarded a perfect 10.0—only the 12th time that’s happened on an album’s initial release. (Notably, one of the other instances was Wilco’s Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, which was released on Sept. 18, 2001, and, like Bolt Cutters, was an album that landed in the midst of a national crisis it seemed inadvertently made for.) From its ominous title and garish cover art on down, Bolt Cutters doesn’t feel like an album that wants to be universally beloved: It’s prickly and off-putting and proud of it. On “Under the Table,” Apple sings about being the ill-behaved guest at a dinner party, the one who has a little too much to drink and starts shooting off at the mouth. But at this point, we’re just happy to have guests, even imaginary ones, and in an emergency, the battle-worn Apple, recounting war stories and full of righteous anger, can make for an oddly comforting presence. “I’m pissed off, funny, and warm,” she rhymes. “I’m a good man in a storm.”

Gathering under one roof to share art with strangers has become a virtual impossibility, and the one Hollywood movie released in the past month has been Trolls World Tour, which is more like a device for subduing children for two hours than something we can take to our collective hearts. Fetch the Bolt Cutters is a salve that meets that unspoken need, willed into mass-art status by the hunger to have something we can share besides uncertainty and fear. Like Tiger King, it’s something that would have been a big deal at any time but feels many times bigger because of the void into which it’s emerged.

Listening to Fetch the Bolt Cutters as I walked around my neighborhood Friday morning, past the shuttered stores and the people in masks, what kept striking me was not what the album says so much as how it sounds, somehow claustrophobic and roomy at the same time. You can hear the space around the instruments, like the echoing drums in “Rack of His” (which inverts the “nice rack” catcall to make it about a man’s guitar collection) or the syncopated snare of “Relay.” On “Newspaper,” a muffled dog bark and what could be the low rumble of a furnace pick up a lazy drumbeat, and then Apple starts humming wordlessly over the top, as if she’s composing the song on the spot over her morning coffee. As revealing as it was to watch Taylor Swift in Miss Americana composing songs in a tiny studio with a single collaborator, it’s also striking how little of that intimacy is polished out of the final product. Apple’s album has a sense of place, as if she’s let you into her home so she doesn’t have to leave it. (It’s telling that Nussbaum’s profile features a moment where Apple is displeased that a recording features too much compression, which tends to increase a song’s punch but makes it sound less lifelike.) The producer Steve Albini once said that few things sounds better than a drum being hit in an empty room, and Bolt Cutters is full of that sound, of rhythms banging off the walls and crashing into each other. The album makes reference to physical abuse and sexual assault, but the betrayal that gets played out at full song length is on “Drumset,” when she returns home to find that her drummer has left and taken her drum kit with her.

On Bolt Cutters, melodies drop in like unexpected guests and leave just as abruptly, sometimes shifting multiple times in the course of a single song. It’s like those dreams where you find a new room in your own house, one that’s always been there but you’ve somehow never seen. The moment you feel like you know where you are, the place changes again. But Apple finds her bearings, if only by getting dragged so far down there’s only one way left to go. “I’ve been in here too long,” she sings on the title track, and if we don’t yet know when we’ll get to throw open our own doors, at least it’s good to hear from someone who knows how to get out when it’s time.

Let’s block ads! (Why?)

[ad_2]